Now we arrive at the bôshi (帽子, sometimes also written with the characters [鋩子]), the continuation of the hamon in the kissaki which runs with a kaeri (返り), the so-called “turn back,” back or up to the mune. The very end of the kaeri, i.e. the point where the hardening reaches the mune, is called tome (留め) what just means “stop.” Please note that some refer with bôshi just to the continuation of the hamon and see the kaeri as a separate element. That means the hamon in the kissaki is the bôshi and the kaeri is the kaeri. But mostly the term bôshi is used to refer to the whole ensemble, i.e. hamon in the kissaki and kaeri and that is how I use this term too. Before we continue with the different bôshi interpretations we have to address the fact that the bôshi is considered as a very sensitive point in kantei. Reason for this is that hardening the kissaki in a proper way – that means in a way which leaves a uniform and controlled hamon and a clearly defined turn back on this rather small and bevelled area – requires some skill. Accordingly, the quality of the bôshi is a very good indicator for the overall quality of the blade because it is rather unlikely that the smith got that right but messed up the rest of the hamon, to put it bluntly. So judging the bôshi is usually the “last fine tuning” in your kantei, or in other words, it either confirms your conclusions drawn from the sugata (production time), jigane (steel), and hamon (school) and allows you to nail your judgement down to a certain smith within a school or at least reassures you to stay with the school you have found out with judging the hamon. Or it is so unique that you have to go one step back and adjust your school judgement by taking another look at the hamon. So far the theory but the topic bôshi comes with a big “but” and that is the polish of the kissaki. That means the same way it is difficult for the smith to harden this part it is difficult for the polisher to polish it, and that has two reason: One reason is the fact that the kissaki has bevelled surfaces, per se not that a big thing because also the ji is bevelled with the niku, but the other reason is the aesthetical concept of the nihontô requires a tip that contrasts with the other surfaces of the blade. Thus the polisher has to tackle the tip in a different way than he tackles the ji and shinogi-ji (you can find a detailed description of the process of kissaki polishing in The Craft of the Japanese Sword). From my own experience I can say that very often the polishing of the tip is kind of neglected, or rather way more emphasis is placed on the contrasting effect than on the visibility of the bôshi. That means in the worst case you just have some scratchy white surface which makes it very hard to see its actual hardening. Well, a good thing at the Japanese sword is that the hamon shows at quite an early stage in polishing so at least you will be able to see something in the kissaki, maybe at least the rough outline of its hardening. But that in turn only works if you have the time and the freedom to look at the blade in a way until you can make something out. At a kantei session you don’t have that time and freedom, i.e. you just can’t walk away with the blade and take it to a different light source where you look at the kissaki for let’s say two minutes.

Back to the bôshi, but a few more things have to be explained before I introduce the different bôshi forms. As seen later there is a special term for a fully or almost fully hardened kissaki but if the kissaki has just a conspicuously wide hardening, we speak of yaki ga fukai (焼きが深い), what means exactly that, i.e. “wide hardening.” Also important for a sophisticated kantei is to judge where the hamon in the kissaki starts to turn back towards the mune. If the kaeri begins rather early after the yokote, we speak of a sagari-kaeri (下がり返り), and if it starts noticeably late, i.e. more towards the very tip of the kissaki, we speak of an agari-kaeri (上がり返り). Please note that this feature can be deliberate, i.e. applied so by the smith, or, in the case of a late starting agari-kaeri, go back to the fact that the kissaki has lost some material. Apart from that, the kaeri can be noticeably pointed, a feature which is referred to as togari-kaeri (尖り返り) or togari-bôshi (尖り帽子). As bôshi interpretations with a pointed kaeri are kind of a small subcategory of their own, I will combine them in the following section under the umbrella term togari-bôshi. You see, it is getting complicated again but also the topic bôshi is actually not as hard to memorize as it seems at a glance. A good tip to start with is to check the interplay of hamon and bôshi. That means, is the bôshi a continuation of the hamon or does the outline of the hardening change with the yokote? If so, chances are high that you are facing a shintô work as in kotô times it was more common to let the hamon run out “naturally” into the kissaki. In shintô times and with the increasing art aspect of the sword, the ji was more seen as a canves where the smith “painted” his hamon, framed by the yokote and the ha-machi. When there was a backwards trend to kotô in the late Edo period, also the hamon continued by trend again into the bôshi. That’s just a rule of thumb, highly simplified, and a thing that has to be put in context with what you have learned so far from the blade. For example, if you think you have a classical kotô Ichimonji as it shows a flamboyant chôji hamon and even utsuri but then you see that the bôshi is suguha or notare-komi, you are probably facing an Ishidô work.

*

3.4 The different bôshi forms

Aoe-bōshi (青江帽子) – Special bōshi interpretation appearing with the Chū-Aoe school which is undulating, shows a tight nioiguchi, and whose smallish ko-maru-kaeri turns relative abruptly and rather pointed and runs back straight back to the mune.

hakikake-bōshi (掃掛け帽子) – Bōshi whose main characteristic feature are hakikake. However, a bōshi with an even larger amount of hakikake is usually referred to as kaen (火炎).

ichimai-bōshi (一枚帽子) – A fully or almost fully tempered kissaki. In some cases part of the outline of the bōshi is still discernible somewhere in the kissaki area. That means, the kissaki is not completely hardened and a kaeri can be seen somewhere very close to the mitsukado (the point where yokote, shinogi, and ko-shinogi merge). The transitions between an ichimai-bôshi and a bôshi with a pronounced yaki ga fukai are fluid.

ichimonji-kaeri (一文字返り) – Bōshi where the kaeri sets off in a straight manner towards the mune and does not run back along the back (or runs back only very little).

jizō-bōshi (地蔵帽子) – Bōshi which appars more or less as midare-komi but with a sharply constricted kaeri area that makes it look like a profile of a statue of the Bodhisattva Jizō. A jizō-bōshi is particularly typical for Mino blades.

kaen (火焔・火炎) – Lit. “flame, blaze.” Very nie-laden bōshi with an abundance of hakikake which looks like flames. Sometimes also referred to as kaen-gashira (火焔頭・火炎頭, lit. “head in flames”).

ko-maru (小丸) – Small roundish kaeri.

midare-komi (乱れ込み) – Irregular, midare-based bōshi.

Mishina-bōshi (三品帽子) – Basically a variant of the sansaku-bōshi but with a kaeri that looks like a narrow jizō-style kaeri. This bōshi interpretation was often applied by smiths in the vicinity of the Mishina school, thus the name.

nie-kuzure (沸崩れ) – A heavily nie-laden bôshi that appears frayed so that it is hard to define the habuchi or outline, or in extreme nie-kuzure cases no outline can be made out at all. A nie-kuzure is often seen on Sôshû blades and at schools and smiths who worked in or were influenced by the Sôshû tradition, for example the Hasebe (長谷部) and Nobukuni (信国) schools, Shikkake Norinaga (尻懸則長), and the Sôden-Bizen, Horikawa, and Satsuma-shintô smiths, just to name a few. The transition between nie-kuzure, much hakikake, and kaen are fluid. A nie-kuzure bôshi might also tend to a nie-based ichimai-bôshi if the entire kissaki is thickly covered in nie.

notare-komi (湾れ込み) – A slightly undulating, notare-based bōshi.

ō-maru (大丸) – Large roundish kaeri.

sansaku-bōshi (三作帽子) – Lit. “bōshi of the Three Great (Osafune) Masters” which were Nagamitsu (長光), Kagemitsu (景光), and Sanenaga (真長) as they were known for applying this kind of bōshi. It is formed by a suguha that runs shortly straight and unchangedly over the yokote and follows then in a slightly undulating manner the fukura to turn back in a compact ko-maru-kaeri.

taki no otoshi (滝の落し・瀧の落し) – Bōshi with a long and rather oblique kaeri which reminds of a waterfall (taki). This kind of bōshi is usually associated with Mihara blades.

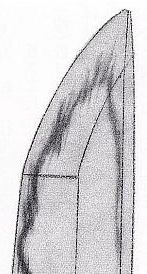

taore-bōshi (倒れ帽子) – Lit. “falling bōshi.” Bōshi interpretation where the kaeri leans towards the ha. A typical feature of Sue-Seki blades (bottom picture left) or of Sa Yasuyoshi (安吉) (bottom picture right). Their bôshi looks like a jizô-bôshi with Jizô’s head leaning towards the ha but with the difference that Jizô’s head is by trend more pointed at the Sa smiths. Please note that a bōshi with a kaeri that approaches the cutting edge due to loss of material is also referred to as taore-bōshi. Thus one has to be careful using this term and specify if in a reference to an altered kissaki or to a characteristic feature of certain smiths.

tarumi-bōshi (弛み帽子) – Lit. “slackening, relaxing bōshi.” Sugu-bōshi that is actually straight or, if undulating, that does not run parallel the fukura. In exaggerated terms, the bōshi is “tired” and has to “relax” and goes thus the short way, which is straight, to the kaeri. For example, a sansaku and a Mishina-bōshi come under the category of a tarumi-bōshi.

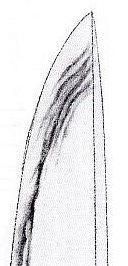

togari-bôshi (尖り帽子) – As mentioned, a bôshi with a noticeably pointed kaeri. A form of the togari-bôshi is the rōsoku-bōshi (蝋燭帽子) which is basically a midare-komi bōshi with a quite pointed kaeri, mostly with plenty of nioi, which reminds of a candle wick (rōsoku no shin), thus sometimes also referred to as rōsoku no shin (蝋燭の芯) instead of rôsoku-bôshi. This bōshi interpretation is typical for Osafune Kanemitsu (兼光) and the Ōei-Bizen school (bottom picture left). And a noticeably pointed kaeri that tends to rôsoku which comes in combination with plenty of nie and a long and rather wide kaeri is typical for Chôgi (長義), thus also the term Chôgi-bôshi exists to refer to his peculiar togari-bôshi interpretation (bottom picture center). And a togari-bôshi is also a typical feature of the Sa (左) school where in their case, the rôsoku part is a hint wider at the base than at the Kanemitsu and Ôei-Bizen schools (bottom picture right).

tora no ago (虎の顎) – Lit. “tiger chin.” Term to refer to a bōshi interpretation seen on blades by Kotetsu (虎徹) and smiths in his scholastic vicinity where the hamon shows a double yakikomi right before the yokote and runs after the ridge more or less parallel along the fukura to a ko-maru-kaeri. The name goes back to the similarity of the yakikomi element to a tiger’s chin.

tora no o (虎の尾) – Bōshi with a more or less long kaeri that runs parallel to the mune and ends abruptly and roundish. This kind of bōshi reminds of the tail (o) of a tiger (tora) and is usually associated with Ko-Mihara blades.

yakitsume (焼詰め) – Also pronounced as yakizume. A bōshi where the hamon runs out without kaeri. The yakizume itself can be sugu or midare-komi and accompanied by various hataraki.

*

Now we are through with the basics (and the terminology) and after a short break – want to post some other articles for reasons of variety – I will continue with the kantei points of all major (and not so major) schools and smiths. Also I have added a new menu with the title KANTEI SERIES to the top page which brings you to all the individual chapters so that you don’t have to scroll back and forth through my entire blog to find a certain post. Thank you so far for your attention and I am very happy about all the positive feedback I get in regards of this series! So stay tuned, there is a lot to come.

Markus,

Many Thanks.

Best wishes,

Paul

>

Hi Markus,

A wonderful and very helpful series and Im sure is an invaluable reference for any one want to further their appreciation of nihonto.

I have question on the differences in concept between the boshi and the rest of the hamon. Can you elaborate on your statement at the beginning of this blog entry, “but the other reason is the aesthetical concept of the nihontô requires a tip that contrasts with the other surfaces of the blade.”? I understand that the boshi, due to it’s physical parameters and size, will need polishing methods more tuned to those surfaces, but this notion of a different aesthetic concept between the boshi and the main hamon is intriguing. What is the different in concept, what is the goal and what are they trying to get across that’s different?

Thank you!

Michael

Hi Michael,

I was referring to the approach of optically setting the kissaki off from the rest of the blade in general, i.e. not to that the boshi itself has to contrast the hamon. In other words, the polisher has to master the balancing act between optically setting off the entire kissaki (from the other surfaces of the blade) whilst making at the same time the hardening patter itself discernible. In other words, too much contrasting usually makes the boshi disappear optically whilst to much emphasis of highlighting the hardening and working out the adjacent ji results in the same finish as the hira-ji what in turn does not set off the kissaki.

Hi Markus

Is possible to give a guide to schools or smiths who made kaen boshi on slender tachi?

Many thanks

Nigel

Hi Nigel,

It is hard to give a usable guide to that issue as there were quite many smiths and schools who applied a kaen boshi on slender tachi, e.g. from the koto Yamato schools over some Mino smiths to later Yamato copies or Yamato-influenced works. Do you own a blade with these features? You can send me some pics to “markus.sesko@gmail.com” and maybe I can narrow it down a little.

Pingback: Explaining Boshi: Defining Characteristics and Diverse Types - Swordis